Leslie Cohen '08: Mar Girgis In Cairo

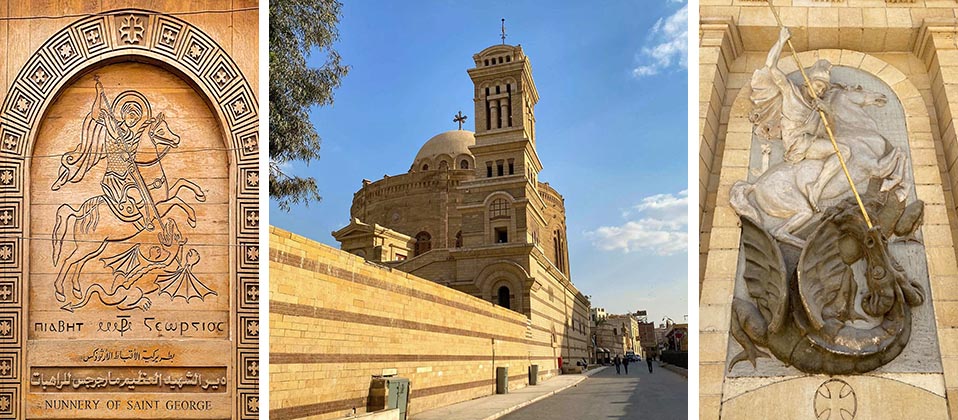

Sign of the Nunnery of St. George (circa 10th century), street view of St. George’s Church enclosed in the Babylon Fortress (fortress circa 1st-3rd century, church rebuilt 1909), and sculpture adorning the Church of St. George depicting the saint as a Roman officer.

MAR GIRGIS -- LOOKING FOR ST. GEORGE IN CAIRO

By Leslie Cohen’ 08

A few stops down the metro line from Cairo’s infamous Tahrir Square sits a sleepy neighborhood with an intriguing window on Egypt’s early antiquity. Mar Girgis—or in English, St. George—is a place I’ve visited several times since moving to Cairo. For a Saint George’s alum, it holds a mystique and poses some questions I’ve been mulling over for a while.

Winding through cool and quiet alleyways, you come next to the Christian heritage sites, which bear an intriguing departure in style from the cathedrals and chapels seen throughout Europe and the United States. Safeguarding these are the walls of the late Roman Fortress of Babylon, erected under Emperor Trajan in the 1st century.

Fixed atop one of the fortress towers is the Church of St. George (rebuilt multiple times since the 10th century, most recently in 1909). Wandering through its lovely nave and contemplating several representations of the Saint in his dragon-slaying pose, I began to wonder how his legend emerged and grew into a symbol adopted and adapted by so many cultures and traditions over the years.

Here in Cairo, St. George is so clearly embedded in the Christian faith that no one would mention him outside that context. Yet at Saint George’s School, which was founded as an Episcopalian school in 1955 but became secular a mere two years later, he is something else entirely. Closer to the myth of King Arthur perhaps, a hero, certainly, but…the story is malleable. We often celebrate the dragon more than the knight, and yet, “Dragon Slayers” is another facet of the school’s identity. So how did this come to be?

What we know about George himself is limited. He is believed to have been born in Cappadocia (modern Turkey) and served as a high-ranking officer in the Roman army. His execution was ordered by Emperor Diocletian, near Lydda (in modern Israel) in 303 AD, for refusing to renounce his Christian faith. He was canonized in 494 by Pope Gelasius, and by the 9th century his Saint’s Day on April 23rd was celebrated throughout Europe.

English kings from the 12th century onward took an interest in the saint, invoking his name and image as protection in battle, and he became patron saint of England under King Henry VIII. This is how George eventually made his way into Spokane, WA.

But the dragon? While we may have to consign any actual dragon-slaying to myth, the story of how George became associated with a dragon is fascinating. The legend goes that George happened upon a town (perhaps in Cappadocia, or maybe in Libya) where a vicious dragon had been holding the villagers hostage for some time. First, it devoured their sheep, and when those ran out, began demanding a yearly human tribute chosen from among the people. When George arrives on the scene, the town’s princess has just drawn the short stick and is on her way to give herself up to the dragon. George of course rescues her, leashes the dragon, and pledges to kill it for the townsfolk if they agree to convert to Christianity on the spot. They do and he does.

So how can a religious icon be so easily adapted into a secular school’s name, spirit, mascot, and colors, without anyone worrying whether its “inherent Christianness” would pose a problem? Perhaps because the meaning behind the symbol is broader and deeper than any one faith or interpretation.

The psychiatrist Carl Jung, for example, who loved his symbols, held that religious iconography (like Mary with the baby Jesus, or Dionysus with his grapes) emerges from a deeper layer of symbolic knowledge that all humans share because they speak deeply to our psychology. We can interpret them religiously, or in a number of other ways.

In the Jungian tradition, St. George’s battle with the dragon represents a battle we all must fight within ourselves, because we contain the hero and the dragon both. To control the dragon is to establish our identity as individuals, against the chaos, raw instincts, and formlessness from which we came. This is very much a coming-of-age assignment. In this version, St. George would not be killing the dragon, so much as coming to terms with it, and learning to work with it throughout life. Some iconographies do come closer to this, with a horseman enveloped by the snake and merely staring at it, or leading it gently by his side.

Is this why the mascot of George and the Dragon still works at a little, non-religious school thousands of years and miles removed from the life of the man in question? Is it why we’re able to celebrate both dragons and dragon-slayers, without getting caught in the contradiction? And is it why I feel a small sense of hominess when I visit Mar Girgis, and look up at an image not too different from one I grew up wearing on a T-shirt to basketball games?

It’s something small, but it brings a sense of satisfaction at the end of all this wondering. And while many things about Egypt make me feel at home—most of all the people who’ve gone out of their way to do so—the little shared cultural artifacts where you least expect them also play a part. Of course, people feel their own sense of ownership over symbols like this one, and we needn’t all agree. But it is lovely how much is shared across cultures and centuries, and how deftly a simple image can remind us of it.

-- Leslie Cohen (SGS Class of 2008) is the associate editor of The Cairo Review of Global Affairs at The American University in Cairo, Egypt.